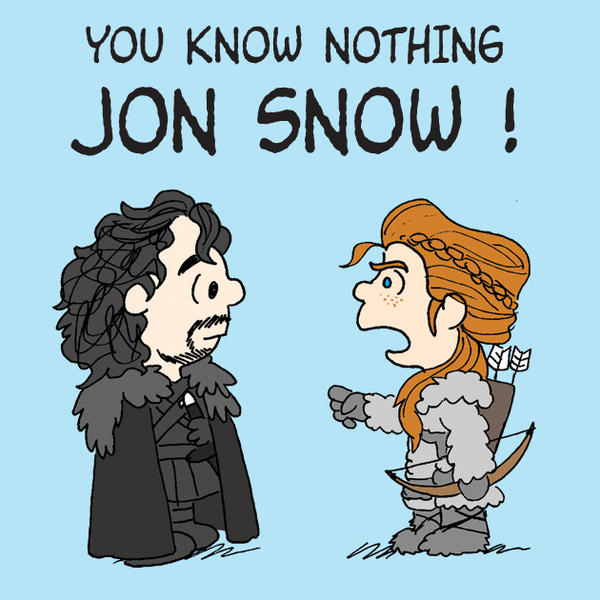

. . . Jon Snow. When's the next book coming out, already?

Anywho:

We think we know. We are so sure we know so much. And we do know a lot. We laugh how previous centuries couldn't understand something as basic as hand washing to prevent death. We roll our eyes that anyone could have thought the sun revolved around the earth. Yeesh, those people didn't have smartphones. Why did they bother living?

Yes, comparatively, we rock. But there is still so, so, so very much that we are ignorant of. There are many things that "science" doesn't really know fo sho. I'm not quoting myself here; I'm relying on Jaime Holmes' "The Case for Teaching Ignorance."

People tend to think of not knowing as something to be wiped out or overcome, as if ignorance were simply the absence of knowledge. But answers don’t merely resolve questions; they provoke new ones.

As Aristotle put it: "The more you know, the more you don't know."

Yet this doesn't apply only in the secular science field. We Jews, as we like to say, are encouraged to question (although it may often depend on which school you end up in). Although, I am noticing that many of my coreligionists are nodding a lot in that "yes, of course" sort of way. They want to know reasons. They even have the reasons.

When one is so sure of the answer, then one stops bothering to question, then one no longer learns.

Our students will be more curious — and more intelligently so — if, in addition to facts, they were equipped with theories of ignorance as well as theories of knowledge.

Anne Lammot said, "The opposite of faith is not doubt, but certainty." Being religious doesn't mean being all-knowing. It actually means saying, "I don't know. Maybe there's an answer. Maybe there isn't. Let's find out which."

Please help SUE the terrorists in court:

ReplyDeletewww.IsraelLawCenter.org

www.causematch.com/projects/shurat-hadin-givingtuesday/

Thank you!