I am in the midst of lions; I am forced to dwell among ravenous beasts—men whose teeth are spears and arrows, whose tongues are sharp swords. —Psalm 57

Today, those words are less often spoken, more often typed. Texts, tweets, posts, updates, statuses, and so forth, can be a roiling, teeming hotbed of fury and shame. With the help of technology, a thoughtless comment can be elevated and escalated to the point where people's lives are ruined.

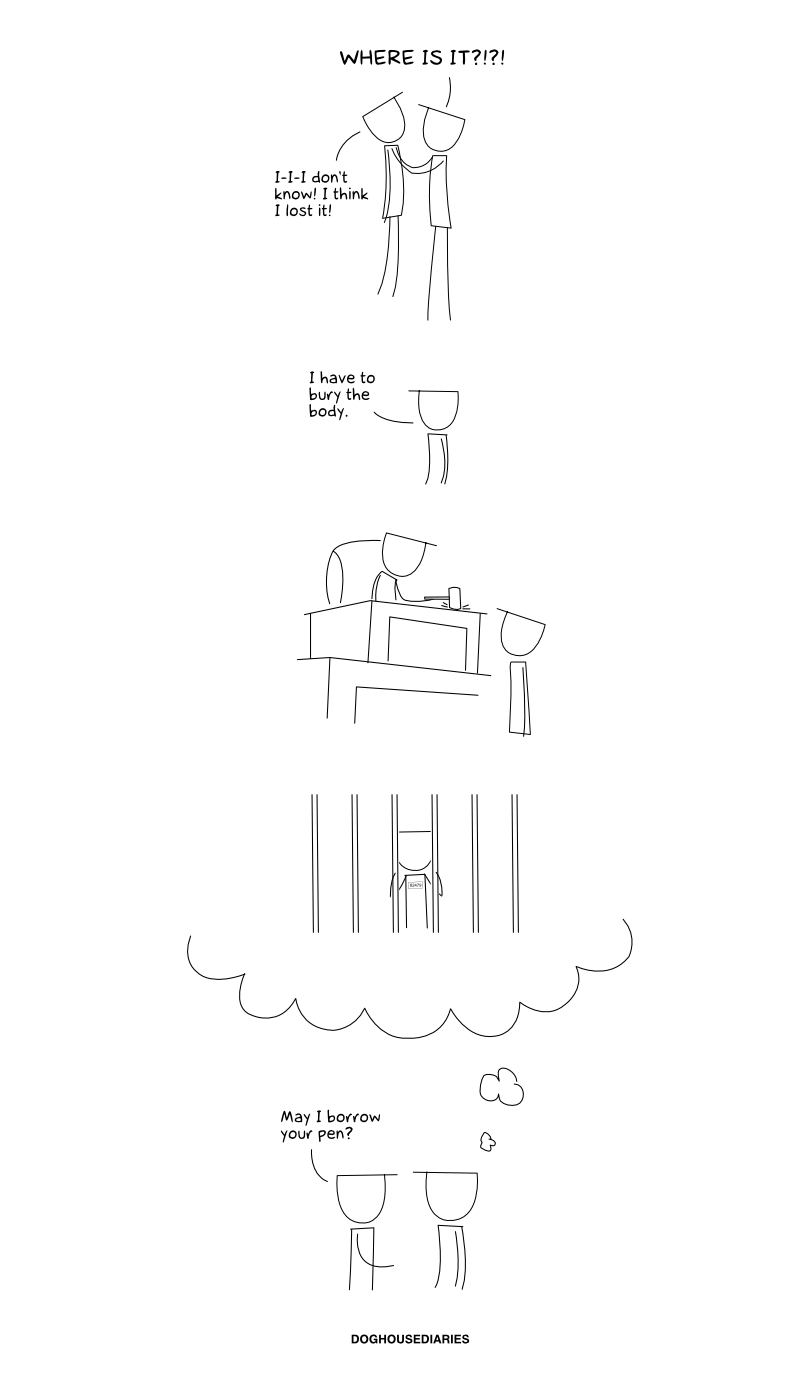

"How One Stupid Tweet Blew Up Justine Sacco's Life" by Jon Ronson lists anecdotes of individuals who, without sufficient thought, spoke, tweeted, or posted a statement or photo that was more offensive than they realized. The backlash and consequences insanely exceeded the severity of the crime.

In some cases, the "muckrakers" that "outed" mindless words with the help of social media were attacked in turn, after these mild offensives were returned with firings and virulent online persecution.

Public shaming is not a new concept. But it now extends beyond one's own small social circle to the entire freakin' world, who don't know the culprit and have no idea what they are talking about. Satire is often taken at face value; humor out of context.

Ronson's conclusion:

When I first met her, [Justine Sacco] was desperate to tell the tens of thousands of

people who tore her apart how they had wronged her and to repair what

remained of her public persona. But perhaps she had now come to

understand that her shaming wasn’t really about her at all. Social media

is so perfectly designed to manipulate our desire for approval, and

that is what led to her undoing. Her tormentors were instantly

congratulated as they took Sacco down, bit by bit, and so they continued

to do so. Their motivation was much the same as Sacco’s own — a bid for

the attention of strangers — as she milled about Heathrow, hoping to

amuse people she couldn’t see.

Why did Sacco tweet so stupidly in the first place? Probably the same reason why I used to constantly post statuses on FB—waiting for the "like" feedback, hoping someone would find me witty and worthy.

Because Sacco tweeted under her real identity, the whiz-bang lash of ostracism was able to destroy her life. But anonymous commenters, subject to no such retribution, can write absolutely anything, snug in their invisibility: "The Epidemic of Facelessness" by Stephen Marche.

When the police come to the doors of the young men and women who send

notes telling strangers that they want to rape them, they and their

parents are almost always shocked, genuinely surprised that anyone would

take what they said seriously, that anyone would take anything said

online seriously. There is a vast dissonance between virtual

communication and an actual police officer at the door. It is a

dissonance we are all running up against more and more, the dissonance

between the world of faces and the world without faces. And the world

without faces is coming to dominate.

I know, when I am distant to an issue, the "obvious" right and wrong side seems all too clear. It is when one comes closer that one sees that matters are not so simple. I try not to take whatever new "outrage" I see online seriously.

Especially since being faceless removes compassion.

Inability

to see a face is, in the most direct way, inability to recognize shared

humanity with another. In a metastudy of antisocial populations, the

inability to sense the emotions on other people’s faces was a key

correlation. There is “a consistent, robust link between antisocial

behavior and impaired recognition of fearful facial affect. Relative to

comparison groups, antisocial populations showed significant impairments

in recognizing fearful, sad and surprised expressions.”

. . . Without

a face, the self can form only with the rejection of all otherness,

with a generalized, all-purpose contempt — a contempt that is so vacuous

because it is so vague, and so ferocious because it is so vacuous. A

world stripped of faces is a world stripped, not merely of ethics, but

of the biological and cultural foundations of ethics.

I find it interesting that those who spew horrible opinions while anonymous "of course" wouldn't say such things in the real world. Being unknown supposedly breeds "honesty." Does that mean that most of humanity, with their actual faces and true names, really don't qualify for that label?

"What Your Online Comments Say About You" by Anna North reports on expert opinion saying that nasty comments don't necessarily come from a place of "truth"; the anonymous trolls could have simply had a "bad day." Nor do they realize that their petty frustrations can be seen by so many.

And as they get more attention, some commenters might become more

self-aware. When media outlets covered Dr. Brossard’s 2013 study,

she took a look at the comments. One reader, she recalled, had indicated

that “now I’m going to think twice because I realize that what I’m

saying, the way I react, and my words potentially can affect other

people.

One reader, she

recalled, had indicated that “now I’m going to think twice because I

realize that what I’m saying, the way I react, and my words potentially

can affect other people.”

“There is research

showing that people underestimate who’s going to see what they say” in

comments sections, said Dr. Kiesler. “Unless they’ve been burned in the

past, they are just not as aware that they’re being observed.”

But if research on

comments continues, maybe that will change. Maybe commenters will become

more conscious of each other and more bound by social norms — for

better and, perhaps, for worse.

In short, think very, very hard before writing or posting pictures. And if in doubt . . . do without.